1. Real Situation: The Invisible Chains of Dependency

Imagine emerging victorious from war in 1945, not only rebuilding Europe economically through the Marshall Plan but also installing invisible mechanisms to ensure long-term dependency on the USA. This is the question we face in 2004: How deeply embedded are the digital traps leading Europe into a future controlled by others?

While the USA had already produced powerful players with a precise plan for the future—and knew exactly what stood in their way, such as the spread of Finder technology—Europe lagged behind. Today, lawyers and historians ask: Was a gang-like structure established around the turn of the millennium to systematically hinder creative minds in Europe? Suddenly, visionaries developing democratic solutions for digital society began to fail. Their silence speaks volumes.

For me, every path of analysis leads to the same conclusion: If I want to save the constitution and democracy in Europe, there is only one way—founding GISAD. Yet to this day, there is no executive management. Even former members of the German Bundestag from the traffic light coalition, whom I approached directly, showed no interest. Why? Perhaps because GISAD would have to take risks—external funding, political resistance, the discomfort of proving the state wrong. I will not guarantee the use of public funds, and I do not trust public authorities as long as they fail to fulfill their own responsibilities.

2. Development Without Obstruction: Europe’s Digital Dream

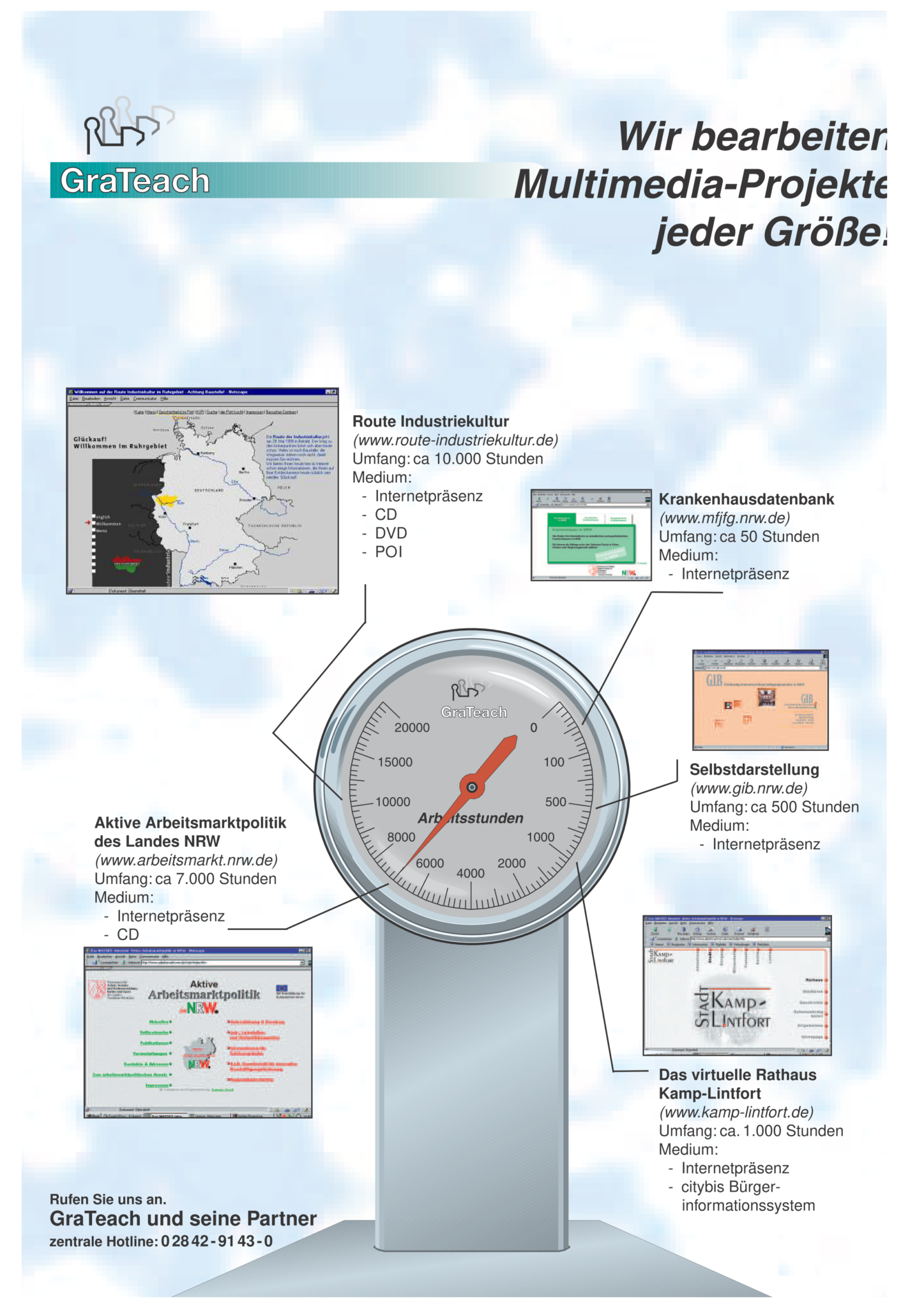

If we had launched the EU-D-S with GraTeach and GISAD in 2004, Europe would stand differently today. The vision of a digital society was already outlined in the Digital Agenda for Europe (2010–2020), but its roots go back to the 2000s:

- Technology for the People: The EU wanted digital participation for all—without roaming charges, with universal broadband, and accessible services.

- Fundamental Rights as a Compass: Data protection (GDPR), consumer rights, and digital sovereignty were to apply online as they do offline.

- Inclusion Through Competence: Digital education, modern administration, and Industry 4.0 for everyone—not just elites.

- A Digital Single Market: Fair rules, free data flow, European standards instead of US dominance.

- Security as a Cornerstone: Cybersecurity to protect Europe from attacks and strengthen its own technologies.

- Innovation with Values: AI, blockchain, and supercomputing—always in harmony with freedom, fairness, and sustainability.

Instead of consistently implementing these goals, Europe remained stuck in the pre-digital era or distinguished itself with only slightly less surveillance than digital autocracies.

3. Perspective from 2026: The Missed Opportunity

Since 9/11, the USA has replaced democracy with surveillance and manipulation—and Europe allowed it. The ten new EU member states of 2004 were deceived: They were led to believe that democracy could be saved with cosmetic reforms, while the digital future was left to others.

What could have been:

- Economic Strength: An EU-D-S would have broken the dependency on US platforms. Investments in European infrastructure would have secured value creation and accelerated EU growth. Independent solutions for e-commerce, search engines, and social networks—similar to China’s Alibaba or Baidu—would have emerged.

- Innovation Instead of Brain Drain: Local tech companies would have grown, and talent would have stayed. Projects could have been built on sovereign systems.

- Social Cohesion: Secure, multilingual services would have bridged the gap between EU states and offered a digital immigration concept.

- E-Government: Reservations about digitizing authorities with US products are justified. A European overall concept would have significantly accelerated the digitization of administration.

- Global Influence: Europe would have set standards—for data protection, democracy, and sustainability—instead of bowing to the rules of US giants.

- Terrorist Attacks (e.g., Madrid 2004): Better coordination of security authorities and citizens through a European digital infrastructure.

Instead: The EU remained a pawn of global powers.

4. GAP: The Billion-Dollar Bill for Missed Opportunities

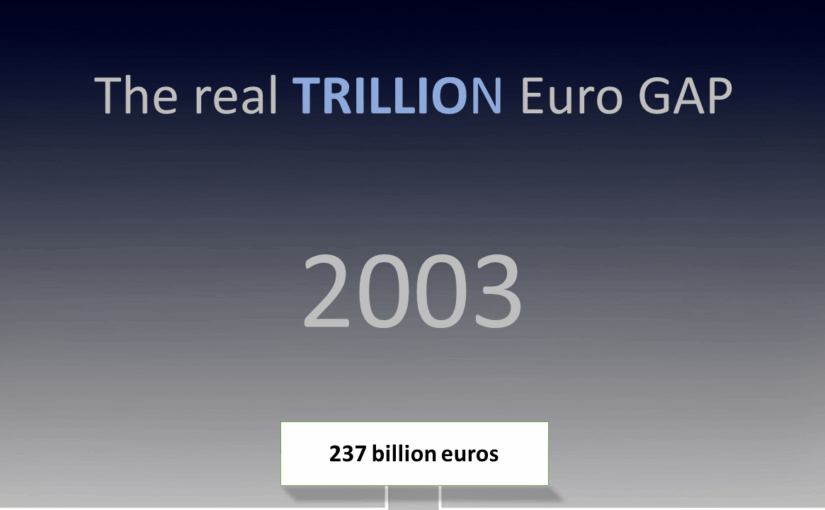

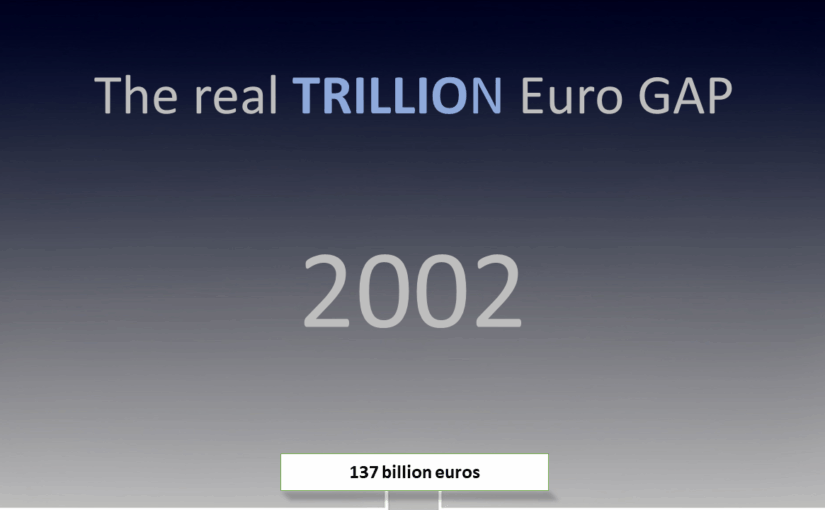

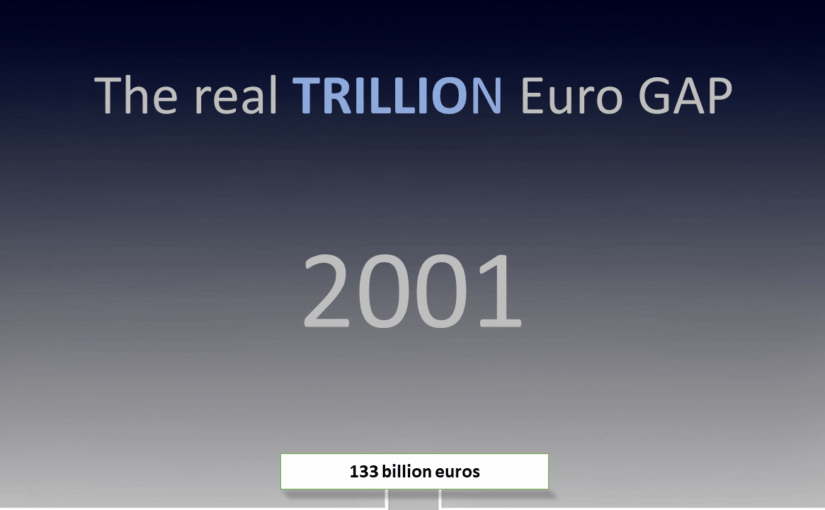

Carryover GAP from Previous Years:

- (2000) Mannesmann takeover: €133 billion

- (2001) Unemployment costs due to blocked GraTeach participation concept: €2 billion

- (2002) Unemployment costs due to blocked GraTeach participation concept: €2 billion

- (2003) Unemployment costs due to blocked GraTeach participation concept: €2 billion

- 2003 GDP: €9,754 billion → €98 billion

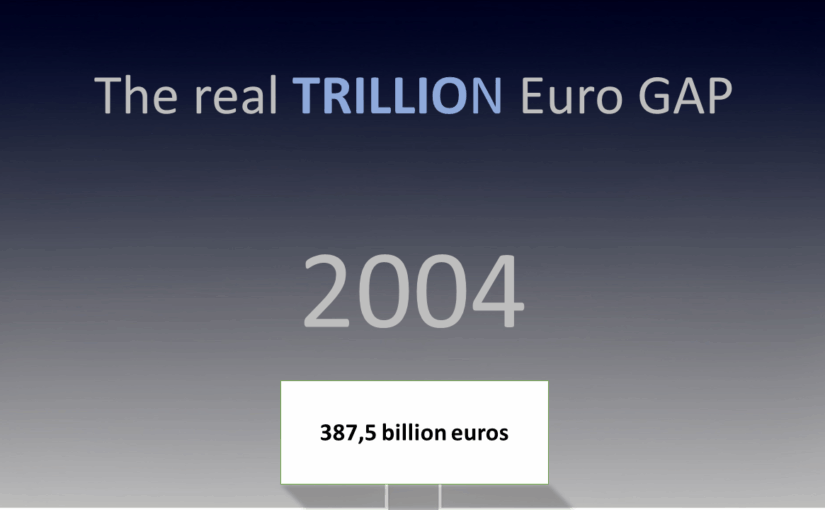

GAP 2004:

- Unemployment costs due to lack of a digital overall concept: €3 billion (Assumption: The creation of flexible, individually adapted digital workplaces would have significantly accelerated job uptake).

- Loss of trust in the economy and digitization (1% of GDP):

- 2004 GDP: $19,423.32 billion × 0.73416 EUR/USD = €14,273.56 billion → €143 billion

- Revenue losses due to US online platforms (30% of €15 billion): €4.5 billion

Total GAP 2004: €387.5 billion

Background: The 2004 EU enlargement brought hope—but without digital sovereignty, it remained incomplete. While Google and Amazon expanded their dominance, Europe lost tax revenues, jobs, and technological leadership. Through tax tricks alone, corporations like Booking.com or Microsoft siphoned off billions.

Conclusion

2004 was the year Europe admitted new states with false promises. Did this make it easier for a rising digital autocracy?

Sources

- What happened in 2004? Events and review of 2004

- LeMO: Timeline 2004

- Timeline 2004 – Review of events and highlights

- The European Economy: Balance Sheet 2004 | EUR-Lex

- Support for the development of European digital content: eContent Programme (2001-2004) | EUR-Lex

- Digital Agenda for Europe 2020 – Wikipedia

- Digital Infrastructure – Cybersecurity – European Digital Policy

- A Europe Fit for the Digital Age – European Commission

- Digital Europe Programme – Shaping Europe’s Digital Future

- A Digital Future for Europe – Consilium

- Revenue comparison of eBay, Google, and Amazon 2004–2023 – Statista

- Google increases revenue and profit – heise online

- 2004 EU Enlargement – Wikipedia

- 20 Years Together: EU Celebrates the Enlargement of May 1, 2004 – Representation of the European Commission in Germany

- „Taxing Digital Corporations Fairly“ (PDF)